Modularity and Cognitive Neuropsychology

The title of today’s article is modularity and cognitive neuropsychology. In today’s article, we will talk about the approaches toward modularity, the concept of what modularity is, and we will also talk about how the field of cognitive neuropsychology helps us understand the relationship between the mind and the brain.

Again just to take a brief stock of what we have been doing till now we know what the definition of cognitive psychology is. The fact is that it is a scientific study of the mind and mental processes. We also looked in the last article at the various approaches that have been taken to understand the relationship between the mind and the brain. But in this article basically, we will talk about this issue of the concept of modularity, which was given by Jerry Fodor and we will try and see how this helps us in understanding the architecture of the human mind. We will also talk about how this field of cognitive neuropsychology, which is a field at a time to understand the damaged brain or which attempts to how different cognitive disorders, gives us a peek into the workings of the human brain.

This article is primarily about two things:

- How do the conceptions of modularity put forth by Marr and Fodor influence our understanding of the Mind-Brain relationship?

- How Cognitive Neuropsychology may help us to understand the nature of the interaction between the mind & the brain?

Marr’s Modular Design

Now one of the central concepts that I will be talking about in today’s article is the concept of modular design. Now David Marr in 1982 put forward this concept as this principle of modular design and he advanced this argument, term of the example of the computer program, and talked about how a particular programmer who is given the task of designing a large and complex computer program will go about this task. Let us say that there is somebody whom we have asked to write a large program.

let’s say the simple task of letting us understand what the different objects are and the shapes in the visual environment, in that particular program, would have to have sub-components. As any typical program.

let us say for example there is a program of the library you have to write a program, that functions as a library, it should allow you to, issue books, it should allow you to register books that are returned in and those kinds of things. Any such programs if you want the program to do some mental activity like looking and seeing shapes, or a typical computer program that you want to just use as a library program, will both need to have sub-components. We have talked about this in the car engine example in one of the previous articles.

today we will also try and see how that example can be applied to an understanding of this human mind and brain interaction. Now the Central idea in this principle of modular design that David Marr gave, was the idea that we need to break down this overall lash program that should be broken down into smaller components each of which does a particular task and each of which is connected to each other in possible ways that help this takes to get completed, ok these are the things you really to do here.

What is the mind like?

Now let us try to apply this to the human mind how the human mind, how this model applies to the human mind, Jerry Fodor takes this approach to this course intending to understand the human mind. So Jerry Fodor takes this how to understand the functional architecture of the human mind. He puts forward something called the modularity hypothesis, the idea the minds may be decomposed into smaller and discrete sub-processes and modules.

Now again coming back to this example of the program, this program is divided into this separate modules or subroutines that can be developed independently of the program, to those of whom who may be from earlier with how writing a program and texting a program work might know it there is a big programmer or a big coder 5000 line code or 10000 line code you have to write, there are people who undertake the writing of this sub modules. And then what is done is basically on these sub-modules or integrated into a single program implemented. As if this was just one program that completes this task, which is as of this program, to complete.

for example, very large software package like Microsoft office, or says for example windows and those of things each of this subroutine you have dedicated set of the programmer who collectively just work on one particular subroutine. Now Marr wrote this with respect to large and complex computer programs. He can actually be applied to how we think of the functional architecture of the mind as well.

for example, if the mind is can be thought of as this simple program that helps this process all this information that we get in this entire environment around here, and all of this possible output that we generate. Then we can think of many sub-modules.

for example – if you walking in a park you are actually undergoing a variety of experiences you smell a lot of odors of the different flowers and would want to recognize them, you would navigate the path, and you would want to walk without bumping into anybody. You might also want to think and decide something, so the point and similarities between three different modules to be doing these things, you would need a module that processes the order and helps you to recognize the object to which order belongs.

You also say, for example, want to have a proper navigational component that helps you walk in this park without bumping into others, and you would to have a particular decision-making kind of module that helps you will decide and whatever happens during a day. And say for example whether the is good or bad, these different kinds of things, so you can take this example in this principle of this modularity that David Marr forwarded and applied to how the mind works to understand and functional architecture of the human mind might be.

Modular Design

Now according to Marr, an very clear advantage to having this modular design, in having a complex system, is divided into this sub-process. Let us take about what these advantages could be.

Now one of the particular advantages of having a system like this, or having this large system, booking down into sub-components or modules of the David Marr has it, has the very important advantage that this makes the system resistant to damage.

for example, if there is one large computer program, and you would want to make a change to one of the lines of this 10000-line program. The point is very possible that if it is just indeed in one single program, changing one line let’s say line number 2501 will change something from the entire program. So if you want to avoid that kind of a scenario, for that what damage too, is they actually have used different modules. So if you have to change something in a module it has a consequence for that module itself. And in that sense you have a system that will not break down, let’s say that one module is not functioning, everything in this function pretty much in this same way, for example, this is something actually which can be explained that our program if it is divided into subcomponents, makes this resistance to damage, any kind of damage for that matter. On the contrary, also say for example if this program is composed of this independent routine it is also possible to see that damage to one of these components does not create for a problem for all the components or entire output of this entire program.

Now applying this view to the human mind or applying this view to the architecture of human mind what can be said is that this sensory transduction processes human senses the eyes, nose, ears, basically each of these sense organs what it does it whatever the information that receives that is converted into some kind of information, that is usable by the senses, by the process which is called sensory transduction, it eventuates a piece of information is transformed into a common perception quotes.

for example, there is some information coming from the eyes, there is something you are hearing and something you say that you are touching. These three sensible inputs will all be converted into a particular perceptional code which will be the common code on which all of these other processors will work. So all of these different sense organs will convert their information into something of a common perceptional code and this is worked on by the higher cognitive processor like decision making, memory, etc,

How does this get evaluated by these higher cognitive processes?

Marr says that this code is then operated on in sequence by the faculties of perception, imagination, reasoning, memory, etc. And each of these faculties, they affect their own intrinsic operations upon the set of input representation. So, what was the different source of information, the eyes, the ears, the noise, the skin, all of them give you different kind of information, and you convert it into the common perceptional code. And then this common perceptional code is worked on by these higher cognitive abilities, like a memory like languages, if you want to talk about it, like say for example Reasoning if you want to decide something about it. And each of these processors works in its own special way. And in some sense irrespective of each other.

for example, that was the idea that David Marr was that limnastic code operation for the particular kind of information will happen independently of the perception processing will happen or independent memory operation that will happen. Now in that sense, it kind of can be a good thing or a bad thing we will discuss this in more detail as we move ahead.

Finally in this way David Marr actually particularly taken with this principle of modular design, because it allowed for a degree of operational independence, memory does not need to depend on perception, reasoning does not depend on memory, it could just operate logically it does not need to take information from the memory. And the point here is wearied the bit of the disagreement with the modular design that already starts scrimping in

, for example, if you want a rather efficient system can be useful. It might be a good thing let us assume that memory does not depend on perception, or reasoning does not depend on your memory, those king of things that David Marr was talking about. The idea was that in this very complex information processing system that is the mind, these different modules can be getting with on your own task, quite independently of your feature, and quite independently of what is happening in the other parts of the brain

So this is what David Marr meant when you are talking about this modular design. Now it already starts feeling a little bit counterintuitive, but be with me as we go through these whole concepts of why modularity was proposed. As we go ahead in the latter, article of this course we will evaluate whether we can apply this principle of modularity, to the way actually cognitive processing takes place because this was something that was given way back in 1982. We know a lot more about, how cognitive processing or how mental functions, operate now. And in that sense evaluate whether this was the correct way of assuming how the mental architecture would be

Other Conceptions of Modularity

So, one of the other very popular formulations of modularity is given by, Jerry Fodor, and Jerry Fodor basically 1983 forwarded which is something known as the modularity hypothesis, Jerry Fodor basically began by discussing, what we called the faculty of psychology.

What is the faculty of psychology?

The faculty of psychology is basically this loosely held set of beliefs that maintains the mind is composed of very many, many different sorts of special-purpose components.

if remember one of the earlier classes I have been talking about what are the different mental functions that, the mind undertakes each of these mental functions can actually if you want theoretically be these different modules. So imagination could be a module, in that visual images could be a module, auditory, or otherwise, imagination could be a module or say for example understanding Shapes could be a module, your ability of reasoning could be a module. So these kinds of things Jerry Fodor actually began discussing.

Marshall

Marshall basically 1984 says that the basis of this idea Fodor was putting forward in 1983, basically could be traced back, to the ancient Greek times of the Greek philosopher Aristotle. Just a quick flashback of what Aristotle was saying.

Aristotle

So Aristotle’s framework basically talked about thinking quite a lot, and his framework basically starts with the considerations of the five senses, we say that the five senses that we have sight, sound, touch, smell, and taste. And each of these five senses maps on to this respective sense organs. So for sight, we have an eye, we have the ear, we have the skin, we have the nose, and we have the tongue for each of these different senses respectively. Eventually, these are the senses which, are the sensory encoding of whatever information is coming in, and in sensory transduction which is basically converting of the sensory information to the form that can be processed by the brain.

Jerry Fodor faculties

Jerry Fodor drawing from what Aristotle had talked about, proposed two kinds of abilities that the human mind or the human brain you might say will have.

The first kind of faculties is proposed by Jerry Fodor where the horizontal faculty. He labeled faculties of perception, imagination, reasoning & memory as horizontal faculties.

What is Horizontal faculty?

Horizontal faculties basically reflect general competencies, whatever the brain generally does on all different, all kinds of information.

for example, whatever processing really cuts across different domains, he is talking about colored and those kinds of things. What all the brain does on every information that comes in, those kinds of faculties could come up under this horizontal faculties category. Say for instance cognitive abilities may be conceived as containing a memory component, all cognitive abilities that is, and therefore, memory can be constituted as a horizontal faculty. Even if I am talking to you about language, if I am talking to you about reasoning, if I am talking to you about imagery, all of these will necessarily have a component memory.

for example, if I ask you to describe the world in 20 sentences, you will definitely use your memory to talk about it. So language has a memory connection, if I talk to you about let us say deciding something, you will actually say – for example, the mental arithmetic example that we took in the earlier classes, comparing 17 x 3 and 14 x 5, you will do some computation and from the memory hold these results, and then compare. So that also has a component of memory.

So this is the way in which these different faculties were supposed to imply, supposed to be involved in whatever the brain is doing, and in that sense at a generic level. And these generic abilities were clubbed under this category called horizontal faculties. So memory in that sense can be constituted as a horizontal faculty in so far as memory constraints are like to others, and with unrelated competencies.

for example, trying to learn a poem by heart, you will need to read the first line, second line, the third line holds it, and then read the fourth and fifth line hold it, and then try and reside it back, so anyways does have memory component involved here.

According to Jerry Fodor horizontal faculties then can be defined with respect to what they do and not defined in terms of what they operate on, these are general processers who are not concerned with say for example, what they are processing. Similar to if they remember we are talking about information processing in the last article, we are talking about how Shannon and Weaver visualize the information processing system, they were not really concerned with what is this information processing system transmitting and receiving. They are concerned with what could be the parameters, and what are the components of the information processing system. Similarly, Jerry Fodor said that horizontal faculties basically are defined with respect to what they are doing and are not what they respect to what they are operating on. So this is one of the ways, in which we think of horizontal faculties.

What are vertical faculties?

Vertical faculty is basically the different kinds of information that are coming, that are really later operated upon by the horizontal faculties. Now the inspiration for this where Jerry Fodor probably came from the month of French musician France Joseph Gall, and Gall had a very interesting conceptualization of the human mind.

Gall’s idea was that the mind is composed of a distinct mental organ, and each mental organ was defined with respect to a specific content domain. I will elaborate on this in just a moment, So for instance, there could be a mental organ that underlies musical ability, a different mental organ that underlies mathematical ability, and a different mental organ let us say that underlies sports ability. So Joseph Gall was actually and France Gall was actually thinking at that point in time, that each ability is associated with a specific organ in the brain. And that is how we conceptualize or actually divided the whole brain into separate portions.

Gall’s Arguments

let us just talk about that in some sense. Gall actually takes these arguments slightly further and proposed that each of these different mental faculties or mental organs could be identified within a unique vision of the brain. And he firmly believed in this, what he did was he basically divided the brain into these particular bumps, he said there are these different bumps in the brain, structural points in the brain which could be interpreted as being associated with particular mental abilities. Each of these regions would embody a particular intellectual capability and the prominence of the bump, how prominent it is, and how it appears, basically would indicate the size of the underlying brain regions.

for example, there is a very important mental function, let us say the ability to do good math, maybe the underlying region or the bump associated with the ability to do math should be slightly larger as sometimes if you think that music is a simpler ability. So the region of the brain devoted to musical ability will be slightly smaller.

There in that sense, here in this, you can see that your, this is what the conception of France Gall was, that these are these different regions, and each of these different regions of the brain are doing something or the other. This is what France Gall said way back in the 1700s and 1800s.

Now in positing these vertical faculties Gall basically provided a critique of the traditional view of horizontal faculty. So he basically said kind of pose this as a constitution of what the horizontal faculties are and what the vertical faculties are. Now, what did he do with this was that the general notion of faculties for memory perception etc, was dismissed in fear of a framework for thinking in which a whole battery of distant mental organs is posited. In which each one has a particular characteristic with respect to memory, perception, etc. So he is saying that let us better divide the brain, not into general abilities like the horizontal faculties, let us talk about vertical faculties which are specific processes and each of these specific processes has a component for memory, has a component for perception. And in that sense, imitation if you notice the last figure should have a component of memory because you would remember what you want to imitate and as a component for designing and stuff like that.

St Gall’s vertical faculties in that sense, do not share, and hence they do not compete with the horizontal resources for memory, attention, intelligence judgment, etc. So there is this conflict between what these general purposes, mental faculties or horizontal faculties or these special purpose mental faculties or these vertical faculties, this is what Gall was talking about.

Fodor’s Modules

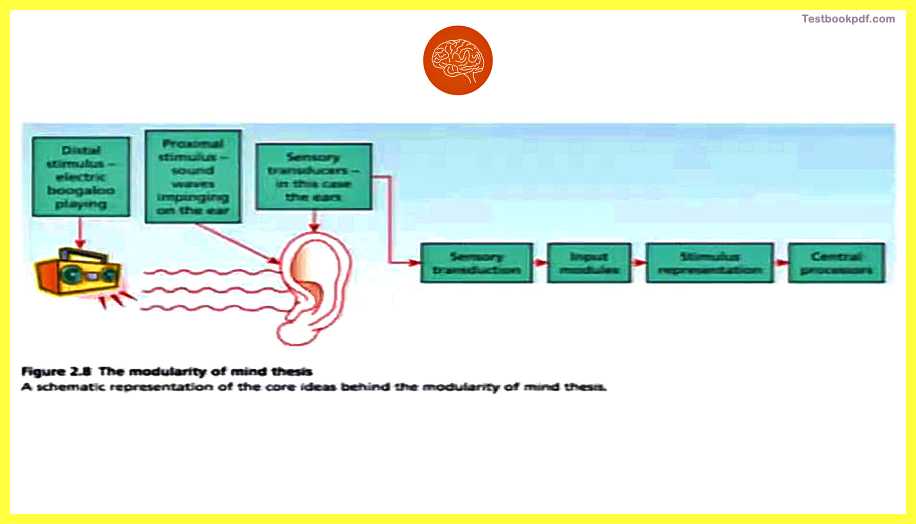

Coming back to what Fodor really wanted us to think. So Fodor wrote this book the modularity of mind in 1983, and a slightly different meaning of modules was introduced by Jerry Fodor. He basically distinguished between what the sensory transducers are, what these input systems, and what are the central processors.

you can think of this in a way, that there is certain information in the world and that information is received by you by virtue of these sensory organs which then convert this information into a form with which the brain can actually deal, so that is the process of sensory transduction. Once that information is converted into a common form after sensory transduction that information has to be acted upon, by the other higher areas of the brain which are your central processors. So hold this example with you and then use it to understand what you are going to take about what Fodor meant with modularity.

The concept of proximal stimulus and the distal stimulus

So in order to understand this, another concept introduced by Fodor was, that the concept of proximal stimulus, and the concept of the distal stimulus. The proximal stimulus basically is what is happening at the sense organs and what is the stimulations that have been received at the organs. This distal stimulus will be what is the actual object that is creating this proximal stimulation.

for example, distal stimulation could be a stereo system that is playing let us say in the next room or in the same room slightly distance from you, and the associated proximal stimulus would be the sound vibrations that you eventually received in the ear. So this proximal stimulation could vary if the stereo is kept very close to you, versus the stereo kept far from you.

The sensory transducers which the sense organs are responsible for taking this proximal stimulus and converting them into a basic sensory code which will be worked upon by the sensory transducers. Now, this code then acts as an input to the corresponding input system. So let us say there is an input system that processes auditory information. Now for Fodor, these input systems are the modules that are referred to in the modularity hypothesis. If you remember what Marr was also the same. These modules have to interact as an interface between the sensory transducers and the central processors. These will be the subunits that we will be working with. So the final decision about what was the distal stimulus in this,

for example, somebody ask you to judge a song that is playing on this stereo. So what was the distal stimulus maybe it has to be made by the central processors? So these central processors are concerned with the fixation of belief and planning of intelligent action.

for example, if a nice song is being played, something that you want to hear, so then you will shift all your retention to it or if something unpleasant is being played and you want to stop it, that kind of decision has to be taken by the central processors. The fixation of the central belief or this fixation of a perceptual belief actually is this act of making a final decision about the distal stimulus, that is what the main job of the central processors would be.

This is a visualization of this entire process, you can see that there is a distal stimulus, and the proximal stimulus and you can see that the end of this entire thing is the central processor which will finally decide how you react to this same function.

All this really interesting thing about thinking, whether you like something or not, whether you heard this before or not, those kinds of decisions basically are taken care by the central processors

Fodor in 2000 also claimed that the operation of central processors actually remains essentially unknown. The black box is still not really clear, in 2000, so for example in much a head, after this modularity hypothesis is proposed still it kind of remains unknown to us.

Modules of Fodor

Let us try to make sense of what these modules are. Fodor says that these modules which are functioning are domain-specific, there are many more modules than sense organs. So the visual system may contain more than one module.

for example, it could be one module of color, one module processing depth, and one module processing shapes and contours. So the entire visual perception system is not a single module, it can also be divided into many sub-modules. Similarly, say for example the domain of language processing there could be a couple of modules one which deals with visual language or one with the spoken language that is auditory language.

A reason take on this basically has been taken by Coltheart, where he says that a cognitive system is domain-specific if it only responds to stimuli of a particular kind. And we will discuss a lot of experiments as we go ahead, one of these examples that we come across is the particular area of the brain, we respond only towards, it is called the visual word form repeats the area of the brain with only two faces which we have faced from face area. So these could be thought of as modules that actually deal with only a particular and a specific kind of stimulus.

What is called modularity and cognitive neuropsychology?

Fodor proposed that these modules are associated with the fixed neural architecture of the adult human brain. So the human brain can be divided into functions in these different modules. Modules exhibit characteristics and specific break-done patterns.

for example, there could be a module about color processing that might go away, there could be a module about speed production that might go away, and that kind of sense. Now if we accept the above two points we are conceding that modules have a fixed neural structure and modules can have specific characteristics of break down etc. Then what we are trying to do is, we are actually assuming rather a critical dependency between the mind and the brain. This is a very interesting part of which cognitive neuropsychology really helps us.

If the brain is damaged, just taking this example further, if the brain is damaged then it is very likely that there will be negative consequences for a particular module that was associated with that region of the brain. And I think this is what you even might have heard of different people, sometimes they are undergoing things like a stroke or something like an accident in which particular and specific abilities are lost, even memory loss happens or loss of language happens, loss of a particular kind of visual capabilities happen. All of those kinds of things are happening consequently to brain damage. So there is that relationship between the mind and the brain, they are to be seen.

What is cognitive neuropsychology?

Cognitive neuropsychology basically, or let us say what cognitive neuropsychologists are concerned with is the operation of disordered brains. brains which have particular kinds of defects, and the assumption here is that much can be learned about this cognitive system, or what the mind is when you actually look at the brains which are not functioning normally, you can look at the broken machine and you can think about this part is not working and this thing is not happening. So this part is related to that particular kind of output, so this is the kind of relationship that we try to maintain, try to deduce when you are actually talking about cognitive neuropsychology. This evidence from these brain damage individuals and the patient from various hospitals can actually provide us converging evidence for particular functional accounts and we also provide critical constraints for such accounts.

for example, you thought that particular area A was involved in reading, and area B was involved in speaking, and you come across the patient whose area is damaged but the person is able to eat completely accurately. It will help you remove that assumption that area A was linked to reading that can happen.

Developmental neuropsychology

Another kind of flavor of cognitive neuropsychology is developmental psychology, Developmental neuropsychology is the branch of cognitive neuropsychology that basically deals with brain disorders that develop as a person ages, and that lead to some form of cognitive impairment that is developmental disorders. There are also acquired disorders that occur during the normal course of development through injury or illness, say for example N-stimulates or stroke, etc, and the example could be some people acquired aphasia which is a loss of language or a particular loss of particular component of language due to stroke or other kinds of illnesses.

Now in adopting this cognitive neuropsychological approach the theorist basically attempts to understand the cognitive deficits following particular or specific kinds of brain damage. One of the things that one does is accept certain key assumptions, what are those assumptions let us say one of those is say for example as Coltheart said you have to have a foundational assumption, that some functional architecture is operating across all human all normal individuals.

for example, eyes or there is a particular area of the brain, let us say area v1 of the event, of the occipital cortex which is the part of the brain which was visual inputs operate in all the individuals, there should be nobody who actually sees through the frontal cortex, that basic assumption one would have to maintain to have any theory about how would mind and brain relationship really works.

According to Coltheart as he says, cognitive neuropsychology would actually simply fail if different individuals had different functional architectures for the same cognitive domain. For example, I just gave also remember that if we are trying to pursue cognitive psychology then we are trying to establish a general principle that applies across individuals. The whole idea of this field is that we are actually reducing theories that would apply to all individuals. If things were so, that there were so many individual differences and each brain is completely different from the other brain, then it is will be difficult to really generate any general purpose theory which would apply across individuals.

The logic behind cognitive neuropsychology

Now the logic behind cognitive neuropsychology is very simple. Cognitive neuropsychology is primarily concerned with the patterns of similarities and differences between normal cognitive abilities and the abilities of these people who have a disordered or damaged brain.

what are the specific abilities of the person with damage in area X of the brain, and what is the cognitive ability of the person who does not have damaging area form on a particular task, so we try and compare this?

So typically the interest is in the performance across the whole battery of generally whole battery of tests is given which will test a different aspect of the particular cognitive function. And the performance of these two individuals, one with the damaging area X and one without damaging area X are tested and compared on these critical parameters, that is how you come to know, that area X was involved in this specific kind of ability under the umbrella of this particular cognitive function.

Now cognitive neuropsychology in that sense is finally distinctive because it really also talks about something detailed analysis of single case studies.

for example, it compares the performance of participants with brain damage, to that of say for example, if there is a patient who has damage as seen earlier in area X, how does this performance compare to the performance of other normal individuals. So we do invest proper importance in a single case as well.

Deficit

Now there could be two kinds of deficits that you find in cognitive neuropsychology, let us talk a bit about that.

Association deficit

The first kind of deficit is your association deficits.

for example, if there is a patient performing poorly on say two different tasks, say for example in understanding written words and in understanding spoken words. These are two different tasks. Now, these kinds of impairments can be said to be associated because they are arising the same function, same person. That there is the same person who cannot understand written words and who cannot understand spoken words.

It might be tempting also to conclude that the performance in both tests depends upon the operation of a single underlying module. So what you can easily say is language is basically involved in both understanding written words and understanding spoken words, this person should have a problem with language. That is why this kind of thing is happening, but there is more to that. We will talk about that in a while.

Disassociation deficit

Another kind of deficit, that one could talk about is the disassociation deficit.

For example, Funnel in 1983 reports one particular patient who was able to read aloud more than 90% of the words but was unable to read aloud even the simplest of non-words.

What are the non-words?

Nonword is something that can is an arrangement of words that can be pronounced, but does not have any meaning. There could be a person who is being able to read aloud all the words, but not able to read aloud any non-words, why should this happen, what is that critical thing missing in this person be. In such cases what we assume is that these abilities are said to be dissociated, reading of non-words and reading of words are said to be dissociated within the same because within the same person one is impaired, but the other is intact.

Now, this deficit in the two tasks in question could also be that of degree. So for example, he could read 50% of non-words, not all the non-words, that could also be one of the things to be considered.

Deficit Examples

Now let us look at these two examples of these two kinds of deficits slightly more closely. In terms of our single dissociation example, we have a case of two tasks that may either arise because of the operation of two different modules one which understands written words, and one which understands spoken words. Or we can think of a non-modular system that contains a single resource, in which basically both of the functions are implied. So there is a stimuli source that would help you understand the single resource.

In explaining the single dissociation then what we can say it is easy to accept the modular explanation. But it can also be explained through a non-modular design, as I said in the example just now. So you can apply the modular explanation that a single body was substantially these two functions that is why the single associated definite or you could say both these modules have been damaged in the same person that is where something has happened. So a modular versus non-modular expression are both feasible here. So say, for example, another way of looking at this is that maybe the two tasks are not equated in their inherent difficulty. So that the single dissociation maybe reflect the different demands on a single resource as we were talking about the modular resource.

We can assume that the dissociation is showing that task A performance is unimpaired or relatively unimpaired whereas task B’s performance shows a substantial deficit, in reading written words or understanding spoken words.

Now by the resource arguments, this can happen if task A is an easier task than task B. So the same ability is damaged and the demands on this ability or the demands on this resources are more by task A and less by task B. So you can say that task A will be damaged, but task B will still be there, because it is only fewer demands on the single resource, as I said task A and the demands on resources and task B, so any damage that results in the depletion of mental resources will have a more catastrophic impact on task B than task A, or we will have a more catastrophic impact on the more difficult task, the one which makes more demands.

what is double dissociation?

Further evidence for mental modules arises when we consider the notion of double dissociation.

for example, if you find a patient in which there are two tasks, task A and task B, and you have two patients, patient 1 and patient 2. So what can happen is say for example double dissociation arises if in one case patient 1 performs well on task A, but perform worse on B. And patient B performs worse on task A and well on B. So you have this kind of dissociation, that there is in the same person, task A is fine, task B is damaged, and on the other person task B is fine, and task A is damaged. So, by comparison of these data from these participants you can actually deduce, that there is no way that task A and task two are linked, and in that sense, you have to expect the modular explanation, that task A and task B, are being observed by two different modules.

Coltheart Example

Now Coltheart basically gives an example, it takes an example of the patient in 2001 and he says that patient A is impaired in comprehending printed words, but normal at comprehending spoken words, and patient B is normal at comprehending printed words but impaired at comprehending spoken words. So this kind of pattern of deficit basically provides you good grounds for concluding that the different modules and underlying text comprehension and speech comprehension, respectively.

More specifically, the double dissociation basically is most consistent with the idea that at least one module that is unique to comprehending either printed words or spoken words is slightly different. So at least one module is unique and is unique modular compares talks about spoken words

Moreover, in the case of double dissociation, such a double dissociation you cannot explain away in terms of only resource sanitation, you cannot say the task A was slightly less difficult and task B was more different that is why this pattern of the deficit has emerged. So in simple terms, if you say for example if task A demanded fewer resources than B as you saw task A performance can remain intact even if task B’s performance is impaired

Now if that is possible, but still reverse pattern cannot occur if the problem is assumed to lie in the allocation of resources in a single non-modular system, something which is happening in the double dissociation case. Any problems in resource allocation will hurt the difficult tasks first,

for example, if you say task A was difficult, task B was easy, then the other example in which task A is damaged and task B is not, you cannot explain that. Because if it is a single resource, then a more difficult task will be affected first. But we saw in the case of patient B, that a different task was damaged, but this more difficult task expired. So that you will not really explain them using a single modular design that kind of forces you to explain or accept this based on two different points.

Coltheart actually takes this and he says that this by no means is various definitive proof of modular architecture. For example, double dissociations can arise in cases where different impairments or the same unified information processing system is there. But for now, we will actually accept the two explanations forwarded of associated deficits and dissociated deficits, and how they can actually help you to deduce whether a particular ability is served by the command module, or by two different modules.

At the End

Now just to sum up, in the article for today we talked about various possible architectures of the human mind using the modularity example something from Marr and also from Jerry Fodor we talked about also how cognitive neuropsychology can help us understand the nature of the relationship between the mind and the brain, thank you.

Read also:

Foundations of Cognitive Psychology Theory

Foundations of Cognitive Psychology Part-2

Approaches Towards Cognitive Psychology

Click here for Complete Psychology Teaching Study Material in Hindi – Lets Learn Squad